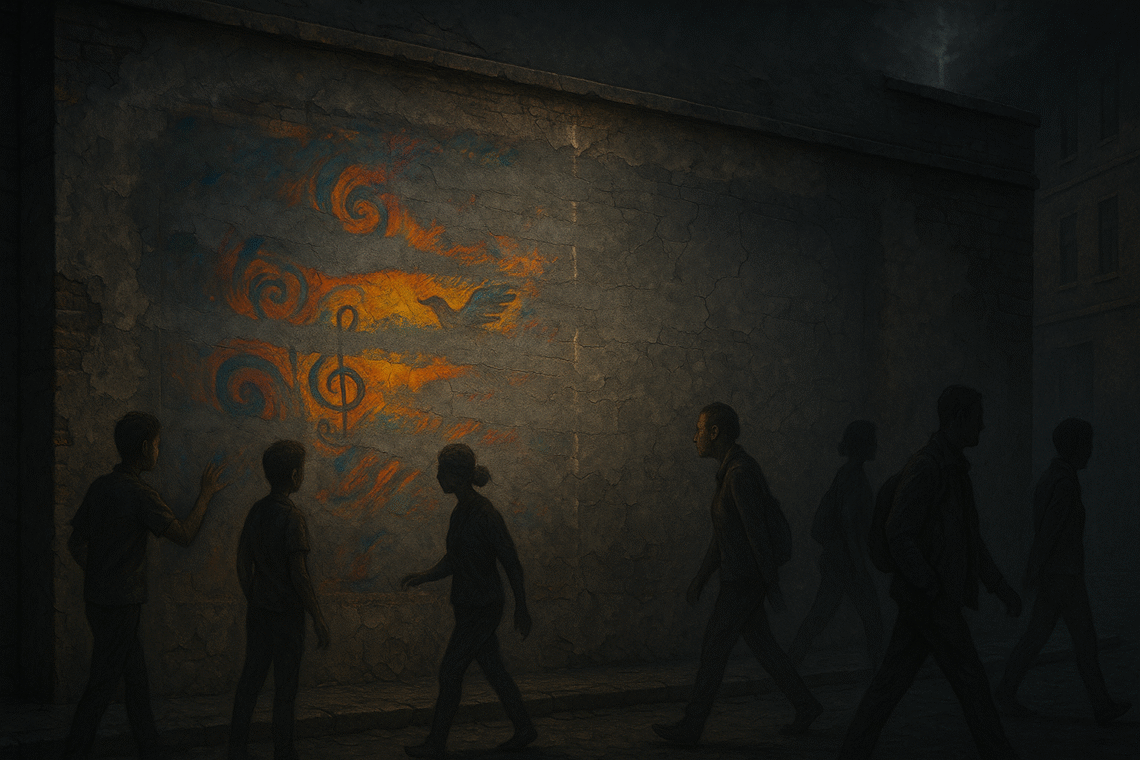

There is an irony, almost tragic in its predictability, in the way societies respond to art that unsettles them. For while art speaks in colour, texture, symbol, and form, the censor responds with the bluntest of instruments: erasure. The mural is whitewashed, the book removed, the play cancelled, the song silenced. What remains is not harmony, but absence—a peculiar quiet in which one is left to wonder what truths were considered too dangerous to be heard.

Censorship is as old as expression itself. Socrates was condemned for corrupting the youth with unsettling questions; Galileo was silenced for gazing too earnestly at the heavens. The impulse behind these acts is not difficult to grasp: human beings fear disruption. We prefer our convictions stable, our social order intact. And when an artwork threatens that equilibrium, the temptation to blot it out becomes powerful indeed.

But to censor is never merely to erase; it is also to reveal. The act of suppression testifies, inadvertently, to the potency of what is being silenced. For why suppress something harmless? If a mural or a novel has no power to disturb, no capacity to persuade, why trouble oneself with its removal? The censor, in attempting to mute the artist, pays them the highest of compliments: acknowledgment of their influence.

This is why censorship so often backfires. The very act of suppression draws attention to the silenced work, endowing it with a mystique it might not otherwise have possessed. The banned book becomes more widely read, the forbidden image more widely shared. To forbid is, in some strange alchemy, to intensify desire. The silenced voice echoes all the louder in the imagination of those who suspect they have been denied something essential.

Yet there is another cost to censorship, one less obvious but perhaps more corrosive. It is the slow erosion of trust. For when authorities silence an artist, they declare, implicitly, that the public cannot be trusted to think, to discern, to grapple with complexity. They treat citizens as fragile vessels, incapable of bearing the weight of difficult truths. And in doing so, they diminish not only the artist, but the very audience they claim to protect.

Of course, we must acknowledge that not all expression is benign. Societies are right to wrestle with the boundaries of speech, particularly where expression incites violence or dehumanises the vulnerable. The line between protection and suppression is not always clear, and the stakes can be high. Yet if we err too far on the side of silence, we risk suffocating the very dialogue that enables a society to correct itself.

Art thrives in the open air. It requires the rough-and-tumble of debate, the clash of interpretation, the willingness of audiences to argue, resist, and even reject. To stifle this process is to deny art its proper life. Worse still, it is to deny ourselves the opportunity to grow in discernment. For freedom of expression is not merely a privilege for the artist; it is a discipline for the community, a shared practice of listening, disputing, and imagining together.

Perhaps, then, the deeper danger of censorship is not the silencing of any one work, but the cultivation of a habit: the habit of turning away from what unsettles us. A society that grows accustomed to silencing its artists is a society that loses its appetite for self-examination. It becomes brittle, fragile, and unable to face the complexities of its own soul.

In the end, every act of censorship poses a question, not only to the artist but to the community: will we choose the comfort of silence, or the courage of dialogue? The answer determines not only the fate of a painting or a poem but the character of the society itself.