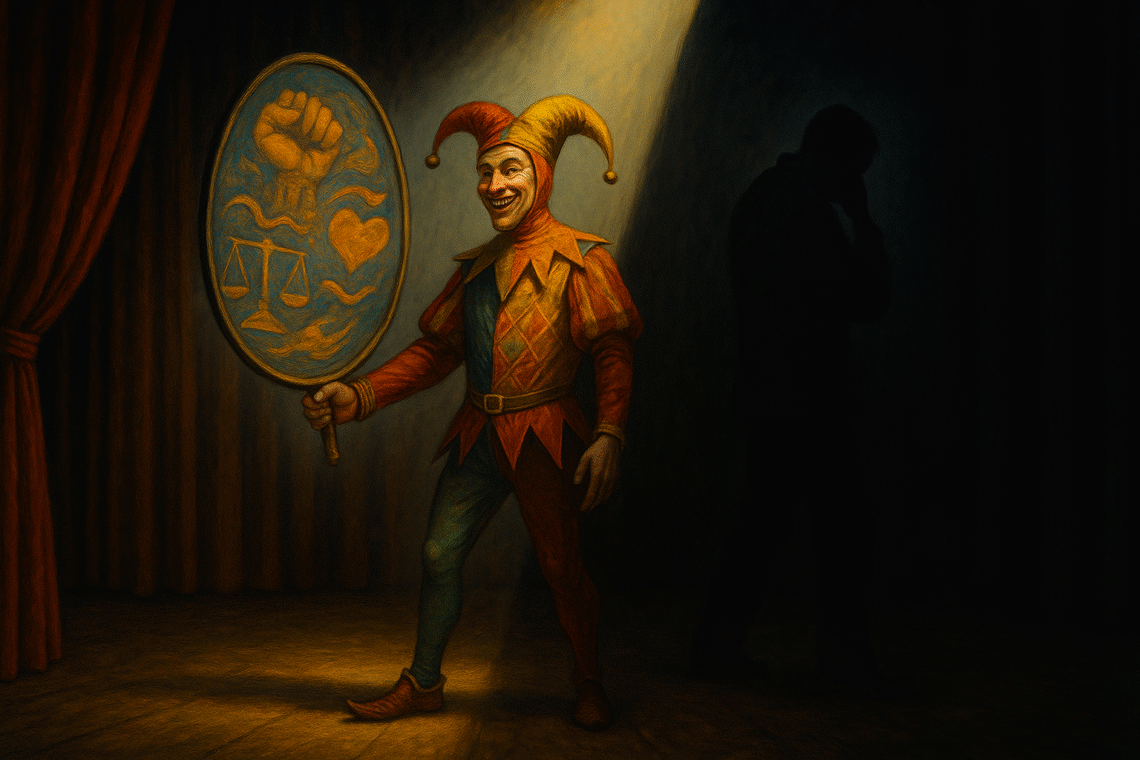

There is a peculiar pleasure in provocation, though few will admit it openly. The artist who unsettles, the satirist who stings, the playwright who exposes hypocrisy—each thrives, in some measure, on the shock of recognition they elicit from their audience. And yet provocation is never a neutral act. It is not mere mischief, like a child pulling faces in a window; it is a moral gesture, a statement of values, whether explicit or implied. Thus arises the thorny question: what, precisely, are the ethics of provocation?

To provoke is to disrupt the ordinary rhythm of perception. It is to arrest attention, to force reconsideration. But the intent behind such disruption matters. An artist might provoke in order to awaken compassion, to expose injustice, to jolt us into moral clarity. Equally, one might provoke for the sake of derision, contempt, or spectacle. The difference, subtle yet significant, lies in whether the provocation expands or contracts our humanity.

The history of art abounds with examples of provocation that proved essential. Consider the political cartoons that undermined despotic regimes, the theatre that ridiculed social pretensions, or the novels that exposed hidden cruelties. These provocations were not mere affronts; they were necessary correctives, instruments of moral imagination. They shocked not to demean but to awaken, not to destroy but to invite reconsideration of what we take for granted.

Yet we must also acknowledge the darker side of provocation. For it is all too easy to confuse cruelty with courage, ridicule with resistance. An artwork that humiliates without enlightening, that wounds without healing, may achieve notoriety but not nobility. Indeed, it risks becoming complicit in the very dehumanisation it seeks to expose.

Here, then, lies the ethical demand placed upon the artist: to consider not only the effect of their work but the direction of that effect. Does it challenge power on behalf of the powerless, or does it reinforce power by mocking the marginalised? Does it awaken empathy, or merely inflame resentment? These questions cannot always be answered with precision, but the asking of them is itself a mark of integrity.

And yet, the artist is not alone in bearing responsibility. The audience, too, must approach provocation with discernment. It is tempting, when confronted with something unsettling, to dismiss it as offensive and move swiftly on. But to do so is to abandon our own ethical work. For we must ask of ourselves: why am I offended? What value of mine has been touched? Is this discomfort an injury, or is it a summons to reflection?

In this sense, provocation is a dialogue. It is a risk taken by the artist and a responsibility taken by the audience. Neither side is exempt from moral scrutiny. The ethics of provocation are not fixed in advance; they are forged in the encounter between creation and reception, in the unpredictable space where imagination meets conscience.

Perhaps, then, the real measure of provocative art lies in its aftermath. What conversations does it generate? What changes does it inspire? What silences does it break? If provocation leaves us merely bruised, it may not have been worth the trouble. But if it leaves us unsettled in a way that expands our sight—if it opens, however painfully, the door to compassion or understanding—then it has justified its boldness.

For provocation, rightly exercised, is not the enemy of society but its ally. It guards against complacency, unsettles false certainties, and demands that we face realities we would prefer to ignore. It is, in the best sense, a gift: a difficult, sometimes exasperating, but ultimately necessary gift for any community that would call itself free.