The first encounter with provocative art is often visceral. A flash of anger, a ripple of laughter, a jolt of discomfort, these are the sparks that ignite when imagination collides with expectation. Yet shock, though useful, is rarely the final word. The deeper purpose of art is not to stun us into silence, but to draw us into dialogue.

For dialogue is where the work of art truly begins. The painting on the wall, the installation in the square, the performance in the theatre, they do not arrive with definitive conclusions. They are not lectures, nor sermons, nor manifestos. They are, at their best, open questions. They say, “Look at me. Now, what do you see? What do you feel? What might this mean?” In this way, art resembles philosophy more than propaganda. It does not tell us what to think; it compels us to think.

This, I suspect, is what unsettles so many about controversial works. Ambiguity is uncomfortable. It denies us the neat categories of good and bad, right and wrong, ally and enemy. It asks us instead to linger in the unresolved, to wrestle with the possible, to entertain interpretations that do not sit easily with our preconceptions. And yet it is precisely in this ambiguity that art achieves its deepest power.

For what is philosophy, if not the disciplined art of asking questions that resist simple answers? Socrates unsettled his fellow Athenians not by offering doctrines but by dismantling certainties. Art, in its own idiom, does the same. It interrupts the monotony of our settled convictions and invites us to dwell in the strange and the new. In this sense, the gallery and the agora are not so distant after all.

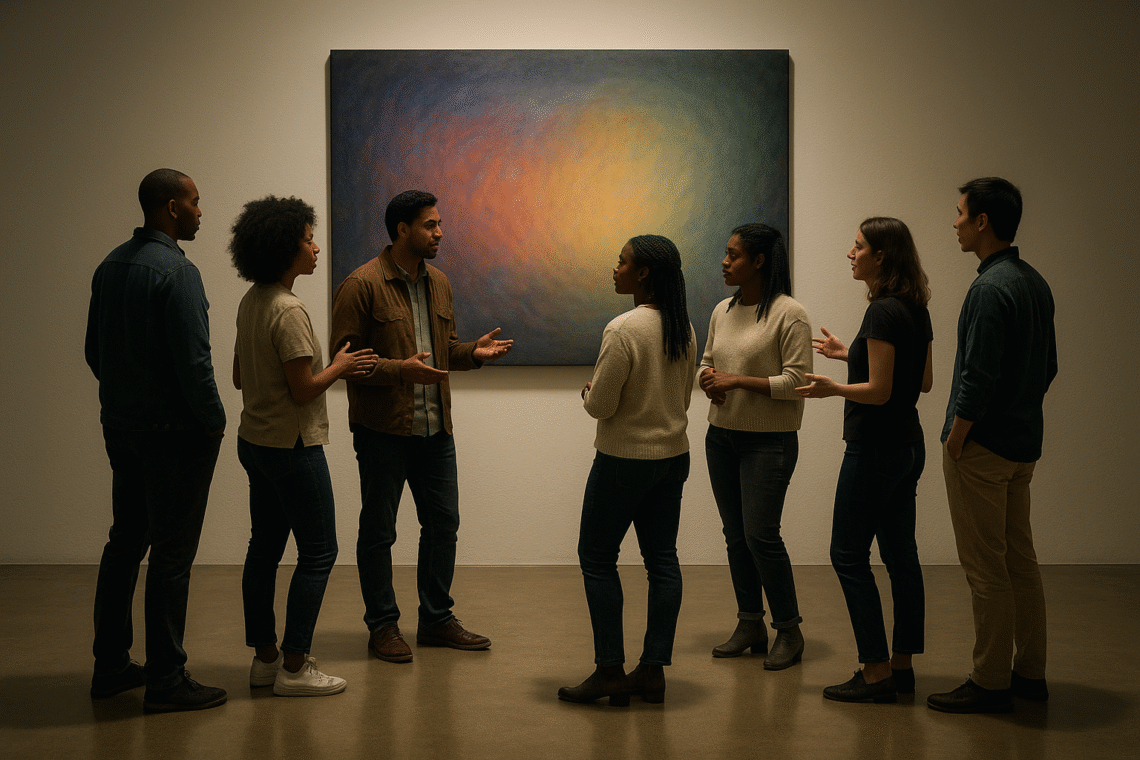

Yet dialogue requires more than a clever artist; it requires a willing audience. To approach a work of art is to accept an invitation, to suspend (if only for a moment) the impulse to categorise, dismiss, or condemn. It is to listen, even when we do not like what we hear. It is to engage, even when we do not agree. Such habits are not easy to cultivate, but they are indispensable to the life of a free society.

Consider the alternative. If we treat art only as shock, something to be applauded or denounced, liked or loathed, we reduce it to spectacle. It becomes another headline, another controversy, another distraction in the endless churn of outrage. But if we treat art as dialogue, we recover its dignity. We begin to ask not only, “What does this mean to me?” but also, “What does this mean to us?” In that shift, something remarkable occurs: art becomes a shared philosophical exercise, a way of thinking together about the world we inhabit.

To live in this way is to embrace art not as a threat but as a partner in inquiry. It is to grant that we, too, might have something to learn from the unsettling and the strange. It is to recognise that our own certainties may not be as complete as we imagined, and that the work of truth is never finished.

Perhaps, then, the true task of art is not to give us peace of mind, but to give us restless minds – minds capable of dialogue, of empathy, of imagining the world anew. If that is so, then the value of art lies not in how loudly it shocks, but in how deeply it teaches us to speak, to listen, and above all, to think.