On Cultivation, Not Spontaneity

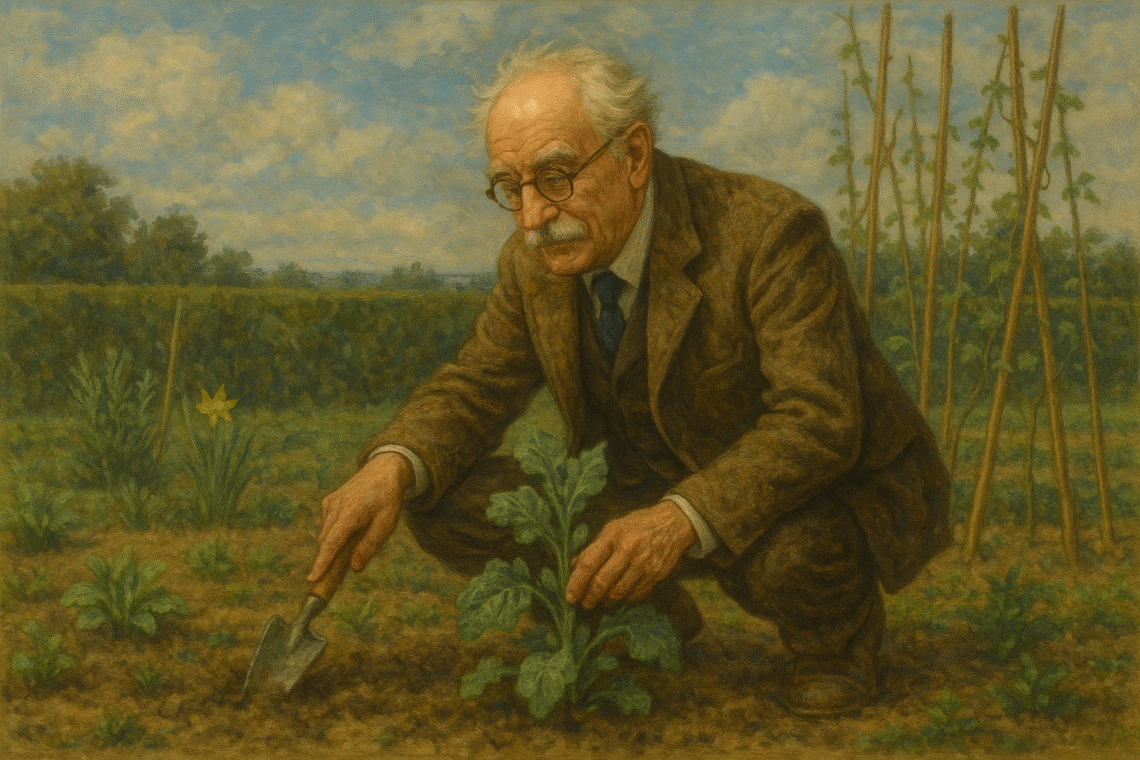

There’s something about a garden in early spring that compels philosophical reflection, particularly if one is both English and in possession of a slightly arthritic back. I was crouched, inelegantly, between a frostbitten rosemary bush and a pair of rather judgmental daffodils when the thought occurred to me: freedom, much like my garden, does not flourish by accident.

This was prompted by an encounter I had years ago with a neighbour, a good-hearted man, fiercely devoted to the idea of untrammelled liberty. He believed in freedom with the fervour of a man recently freed from boarding school. In his view, the highest form of personal expression was to do precisely as one pleased at any moment, and this extended to his property, which looked less like a garden and more like a post-apocalyptic experiment in anarcho-botany. Chickens wandered freely, competing with courgettes for dominance. The lawn, if one may call it that, was waist-high and allegedly “rewilded,” though I suspect that was a polite way of saying he’d lost the mower.

Now, far be it from me to deride a man’s horticultural convictions, but I couldn’t help noticing that while he was preaching freedom to the tomatoes, they seemed rather less fruitful than mine.

And that, dear friend, is the crux of the matter. Liberty is not license. It is not the unchecked sprawl of self-will. Freedom, paradoxically, is a cultivated thing. It requires structure, like a vine needs a trellis, or else it becomes little more than an unruly mess of potential.

Think, for instance, of a pianist. The freedom to play Chopin beautifully does not come from hammering randomly at the keys in a fit of creative spontaneity. It comes from years of scales, patient teachers, and hours spent with aching fingers and a metronome that sounds like the ticking of eternity. Likewise, the freedom to write a sonnet, to speak wisely, or to cook a perfect soufflé, each of these so-called “liberties” comes not from doing what one wants, but from doing what is needed until one wants it.

The same is true in the moral life, and in the life of a society. True freedom is the result of long cultivation. It grows where there is responsibility, rhythm, restraint. A free people must be a trained people, not in the sense of submission, but in the sense of moral muscle memory. We must, quite literally, be schooled in liberty.

Which is why I get nervous when we confuse spontaneity with authenticity. Don’t misunderstand me, I’m fond of the odd burst of whimsy. But the notion that our truest selves are whatever bubbles to the surface in the moment is a dangerous piece of compost. It forgets that many of our impulses, left unexamined, are less expressions of freedom than of appetite, or trauma, or boredom, or the lingering influence of our Aunt Susan, who really shouldn’t have been given the sherry decanter.

No, liberty worthy of the name is not discovered in a sudden flash of personal sovereignty. It is grown, weeded, and watered over time. It is apprenticed to discipline, to memory, to virtue. Like a garden, it requires seasons of rest, of pruning, and of gentle but persistent care.

This is why the ancients were so obsessed with paideia, the education of the whole person. And why the founders of free societies (at their best) did not just demand rights but also responsibilities. They understood that freedom is not the starting point of a civilisation, but its reward. It must be earned, then guarded, then offered anew to each generation like a well-tended plot of earth.

So I return each spring, slightly stiffer than the last, to my little garden. Not because I enjoy the digging (I don’t), or because I have any particular affection for slugs (I really don’t), but because there is something deeply hopeful about cultivation. It reminds me that freedom is not a thing to be seized and consumed, but a thing to be stewarded.

We live, after all, in an age where spontaneity is overvalued and formation is underappreciated. But no flourishing thing ever grew merely by being left alone. Not a soul. Not a society. And certainly not my tomatoes.

What part of your life, or your society, might need less spontaneity and more cultivation? Are there virtues or disciplines that feel laborious now but may one day flower into true freedom? Where might your liberty be waiting for a little tending?