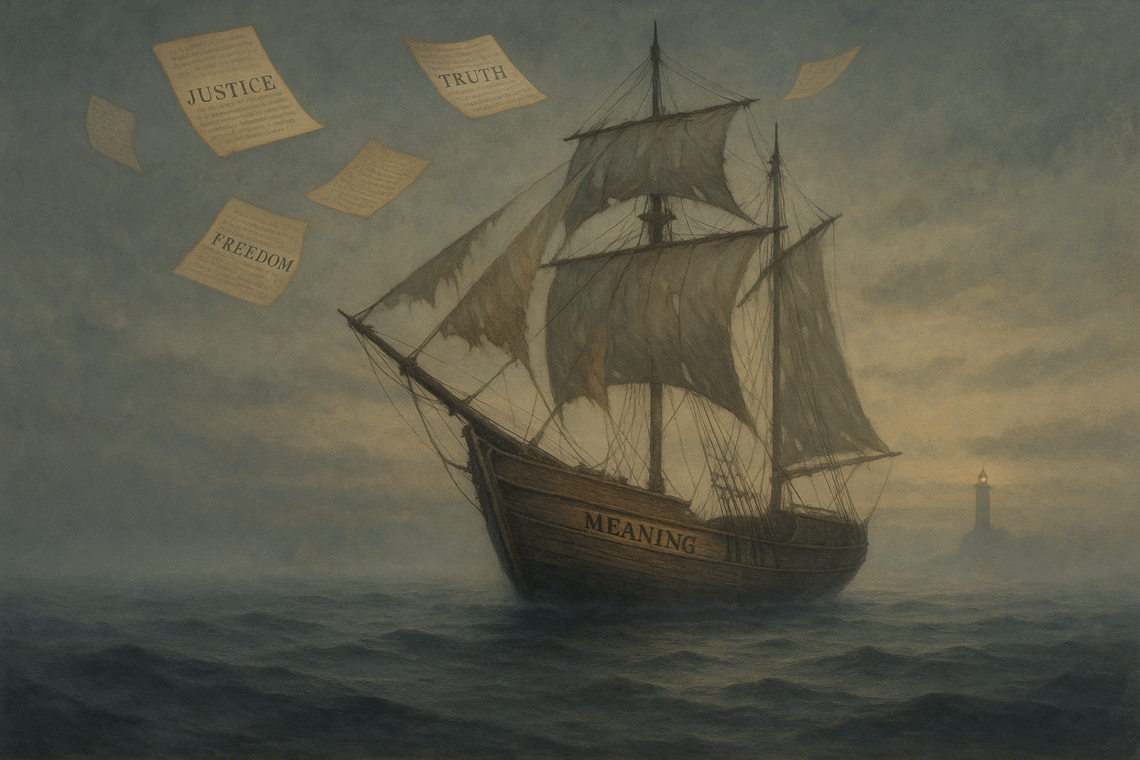

Words, like ships, are always moving.

They slip their moorings, drift on currents of culture, and sometimes arrive in strange harbours bearing new cargo. What began as one thing, solid, clear, becomes, over time, contested, layered, and volatile. This is the strange fate of language: it evolves. But not always innocently.

Take the word freedom. In one era, it might mean the right to assemble, speak, or worship; in another, it might be invoked to justify deregulation, conquest, or personal license at the expense of the common good. The word has not changed in spelling—but its meaning has been negotiated, shaped, even weaponised.

Or consider justice. Once the province of philosophers and prophets, it now risks becoming a brand—hollowed out by hashtags or inflated by polemic. It still stirs the soul, but one is never quite sure which soul is being stirred, or to what end.

This is semantic drift: the slow, often invisible process by which words come untethered from their origins, and float toward new, and sometimes conflicting, destinations.

At first glance, this seems benign, maybe even natural. After all, language is a living thing. No word remains fixed forever. Shakespeare would scarcely recognise our use of “gay,” “awful,” or “literally,” and he was no slouch when it came to stretching meanings.

But not all drift is passive. Some of it is engineered. Behind the gentle currents of linguistic change are often unseen hands, political, commercial, ideological, nudging the vessel for their own ends.

In recent decades, we’ve witnessed entire vocabularies altered by design. A corporation rebrands “layoffs” as “rightsizing.” A government describes civilian casualties as “collateral damage.” An educational institution transforms “failure” into “insufficient progress.” It sounds better, but the reality remains unchanged, if not obscured.

This isn’t simply spin. It’s a quiet battle over the moral imagination. Control the word, and you influence the world it names.

Here lies the central question: Who gets to say what a word means?

Is it the lexicographers? The politicians? The pundits? The people?

Language does not evolve in a vacuum. It is shaped by power, and often for power. To win the war over meaning is to win the power to define reality itself. It is to declare, in effect: This is what counts. This is what matters. This is what is true.

One need only look at the modern contest over words like woman, truth, violence, safety, or patriotism to see how high the stakes have become. In many cases, the dispute is not simply about semantics, it is about whose world we are living in.

The risk is that we become too cynical to care. That we assume all language is manipulation, all definitions are political, and meaning itself is an illusion. But that, I think, is the final victory of those who wish to confuse rather than clarify.

We must not abandon meaning to those who would twist it.

Instead, we must become caretakers of our language. Not reactionaries, clinging to a fossilised past, but stewards, committed to understanding both the histories and the futures of our words.

To do this is slow work. It requires etymology and empathy. Philosophy and poetry. A willingness to listen, and a willingness to resist.

It means recognising when a word has been co-opted and choosing to either defend its original integrity or help it evolve in ways that still honour truth.

Sometimes, the most radical thing you can do is to use a word correctly.

Sometimes, it is to lovingly redefine it.

So here is today’s act of linguistic stewardship:

Choose one word, just one, that you feel has lost its way. Look up its etymology. Read how it has been used over time. Consider how it functions in the present. Then use it in a sentence, paragraph, or conversation with the weight of that full history behind it.

Speak it as if it matters, because it does.

In the war over meaning, every sentence is a skirmish. Speak yours with care.