Stillness is a word that ought to come with a warning label. It sounds so benign, so tranquil, like the final pose in a yoga class, or the view from a hillside bench. But try practising it in earnest, and you’ll find yourself confronted by an uninvited parade of inner turbulence: unpaid bills, yesterday’s regrets, that dreadful thing you said in 2003.

I once fancied myself as being good at stillness. After all, I spend a fair amount of time alone with books and tea, and I’ve been known to gaze wistfully out of windows, at walls or the mosaic floor! But those are not stillness, not really. They are distractions draped in dignity. Stillness, as I’ve come to understand it, is something much deeper, it is not simply the absence of movement, but the presence of attention.

My real initiation came one afternoon in a stone chapel on the edge of the Lake District. I had been invited to join a retreat, one of those silent affairs where everyone wears sensible clothing and no one makes eye contact. I agreed, mostly out of pride. How hard could it be to sit still for half an hour?

Well. After the first three minutes, I was convinced my leg had fallen off. By minute seven, I had reviewed my entire grocery list and mentally redesigned the kitchen. At minute ten, I was perilously close to standing up and confessing my sins just for something to do. But then, somewhere around the quarter-hour mark, a curious thing happened.

My thoughts began to tire. The mental noise grew quiet, like a party slowly winding down. And into that hush crept something… different. I noticed the sound of the wind pushing gently against the old chapel doors. The dust motes moving like cathedral processions in the shaft of afternoon light. My own breath, unremarkable, but steady, like a kindly companion who had been with me all along.

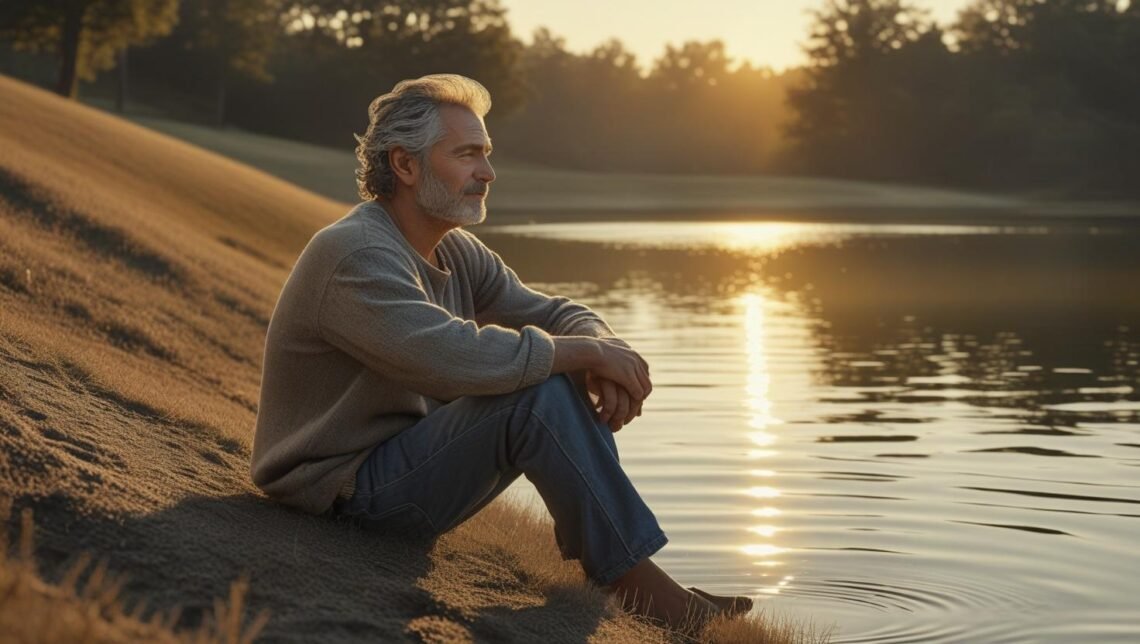

Stillness, I realised, is not about escaping the world. It is about entering it more fully. Not the world of headlines and notifications, but the world beneath and within: the world of breath, of heartbeat, of presence.

We are, most of us, afflicted by a sort of existential fidgeting. We’re trained to equate motion with meaning. We dash from one thing to the next with the faint but persistent dread that if we ever stop, something terrible will catch up with us—grief, perhaps, or truth, or the uncomfortable knowledge that we don’t quite know who we are when no one is watching.

But here’s the secret: stillness doesn’t expose us, it restores us.

In stillness, we meet ourselves not as projects to be improved, but as creatures to be held. We discover that our value is not in our doing, but in our being. We remember, quite simply, that we are, and that this, in itself, is enough.

Of course, stillness takes practice. It is an acquired taste, like jazz or strong coffee. It will not shout to be noticed. It waits. It invites. It does not perform. And in this way, it resists everything our culture celebrates.

But precisely because of this, it is subversive. In a world obsessed with acceleration, stillness is a kind of civil disobedience. It says: I will not be owned by urgency. I will not outsource my peace to a screen. I will not sprint through life without ever arriving in it.

There is a reason why so many spiritual traditions place such reverence on the practice of stillness. It is the posture of listening. The soil where wisdom grows. The space where the soul unclenches.

So I commend it to you, not as a task to conquer, but as a grace to receive. Five minutes by a candle. A morning walk without headphones. Sitting still long enough to hear the robin sing and the neighbour’s dog remind you of its existence.

And if you find, as I do, that your thoughts wander, that your foot falls asleep, that you remember an embarrassing moment from your teenage years and flinch visibly—fear not. This too is part of the practice. Stillness is not perfection. It is presence.

Let us learn to be still, not because we are idle, but because we are alive. Not to retreat from the world, but to enter it more deeply. And in that stillness, may we discover something quietly glorious:

Ourselves, awake and whole and enough.