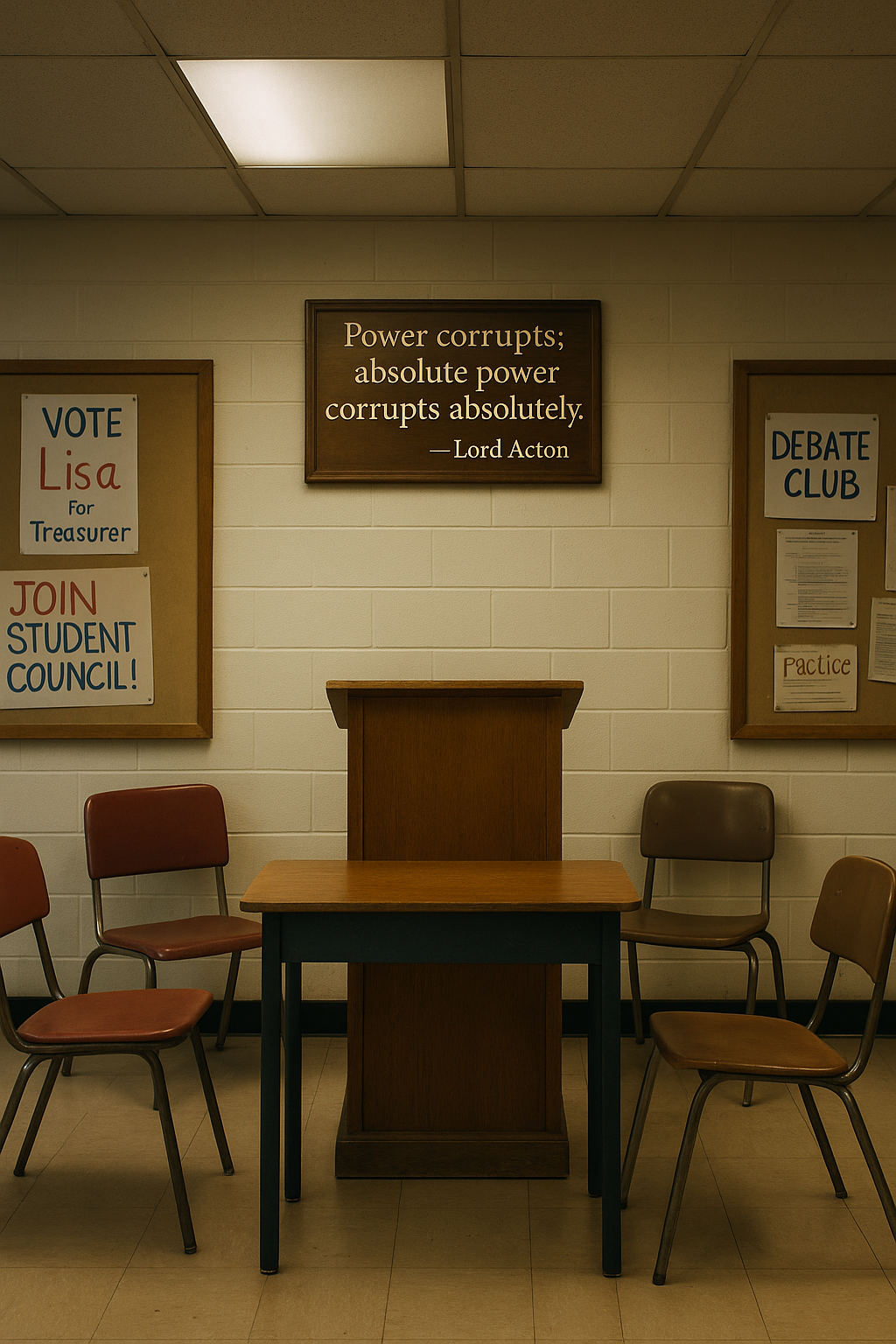

“Power corrupts; absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

— Lord Acton (and also the slightly faded plaque above the radiator in the student council room)

It is an odd thing, really, to be shaped by a sentence nailed to a wall. And yet, there it hung, austere and slightly self-important, presiding over our teenage debates like a Roman senator watching plebeian squabbles from a marble perch.

We fancied ourselves statesmen, of course. Governors of bake sales, arbiters of locker-room disputes, and once—disastrously—reformers of the school canteen menu. Yet beneath our adolescent theatrics lay something far more serious: an apprenticeship in power.

What does it mean to wield influence over others? To make decisions that affect the course of lives, even in small ways—seating plans, speech schedules, or the mysterious disappearance of double chocolate muffins on Thursdays?

The danger, Acton warned us, is not simply that the powerful might be tempted to misuse their position. No, the danger is more insidious: that the possession of power might change the very soul of its bearer. That power, unchecked, is not merely a tool but a solvent—dissolving conscience, distorting perception, and unmooring one’s moral compass.

And yet—here’s the rub—we must wield power. For to abstain entirely is itself a kind of abdication, and the vacuum will surely be filled. If not by us, then by those less thoughtful, less cautious, or, God forbid, less fond of the Socratic method.

So what is the way forward? If power is both necessary and dangerous, how might one hold it responsibly—like a sword that must not be drawn too often, nor gripped so tightly that it cuts the hand that holds it?

From those early days in student council, I learned that power is best understood not as a possession, but as a relationship. Not something I had, but something I was entrusted with. And trust, unlike authority, can be withdrawn—quietly, swiftly, and usually without warning.

The best wielders of power are those who treat it like sunlight: not to hoard it, but to help things grow. Teachers who encourage curiosity rather than conformity; mentors who open doors instead of standing in front of them; leaders who speak softly, not because they are timid, but because their authority speaks louder than their volume.

In those council meetings, beneath fluorescent lights and the faint aroma of floor polish, I began to notice something else. The people who truly moved things—who changed minds or softened opposition—were rarely the loudest. They were the ones who listened best. Who remembered names. Who spoke last, not because they had little to say, but because they understood that timing matters more than volume.

And so I offer this, dear reader, as our point of departure:power is neither friend nor foe, but a flame. Held rightly, it warms and illuminates. Held arrogantly, it scorches. And held too long, it burns the holder from within.

In this series, I shall explore the different faces of power—its uses, misuses, and redemptions. I shall wander from boardrooms to classrooms, pulpits to protest lines, from the intimate politics of family life to the grand theatres of religion and governance. But I shall begin here, in that little room of my youth, where power first introduced itself to me not as dominance, but as a question:

“What will you do, now that others are watching?”

A question, I daresay, we never quite stop answering.