On the Paradox of Freedom

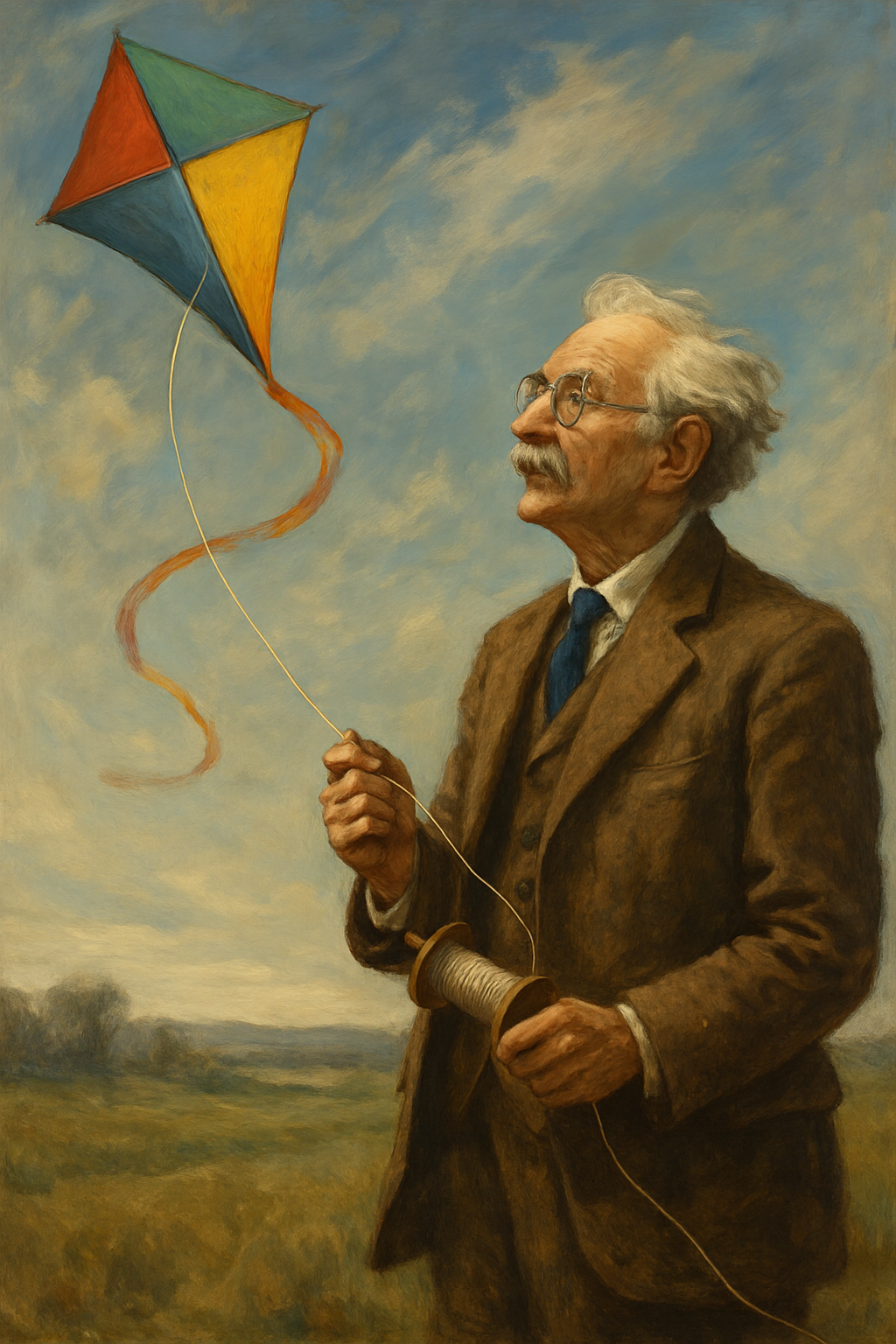

It was on a blustery spring afternoon, the sort that makes one question whether April has mistaken itself for November, that I found myself in a wide open field, flying a kite with my godson. He, being six and unencumbered by philosophical metaphor, was primarily concerned with whether it would fly. I, being somewhat older and tragically inclined toward metaphorical thinking, was more taken with the strange alchemy that allowed this scrap of fabric and stick to lift skyward.

We had been at it for some time—he with untamed enthusiasm, and I with the creeping awareness that my knees no longer approve of sudden exertion—when it occurred to me: the kite only flew because it was tethered. Let go of the string, and it might soar a few seconds higher, yes, but then it would falter, spiral, and tumble into the grass like I did last year while attempting yoga.

There is, I think, a lesson here. Freedom is not the absence of all restraint. It is not flight for its own sake. Rather, it is that curious state in which one is both grounded and aloft, held and released, wild and connected. Freedom depends, paradoxically, on the right kind of tether.

Now, I admit this is not the sort of thing political philosophers say during campaign season. There, the word “freedom” tends to mean unbounded choice, unlimited speech, and the curious notion that the highest good is to do exactly as one pleases. That, I suppose, has its place. But as any kite-flyer, pianist, or monastic gardener will tell you, that sort of freedom is a fragile thing. Left to itself, it collapses under the weight of its own looseness.

What we need, instead, is a more muscular kind of liberty. Not the freedom from all bonds, but the freedom within them. The freedom that grows, quite surprisingly, in places where there are rules, rhythms, responsibilities—and yes, even relationships. Not every binding is a prison. Some are the very reason one can rise.

This is the wisdom the ancients knew, and which we, in our modern zeal for autonomy, are in danger of forgetting. The Stoics understood it. The Benedictines practiced it. Even the early liberals, Locke and Mill and their ilk, hinted at it—though perhaps with less poetry than the matter requires. They saw that freedom must be cultivated, not simply declared. It must be taught, tested, and lived into over time.

And if this is true for the individual soul, it is doubly true for a society. A free society is not one in which each citizen lives as though their neighbour were a distant star. It is one in which people are connected by invisible threads—civic trust, shared memory, a common language (or at least a shared tolerance of each other’s idioms), and a tacit agreement to stop at red lights.

Indeed, we might say the strength of a free society is measured not by how far each person can fly, but by how well we hold the string for one another.

Now, holding the string is not always glamorous. It’s not the sort of thing one puts on a résumé. But someone must do it. Someone must teach the children what freedom is and what it isn’t. Someone must tend the institutions, however creaky and outmoded they may appear. Someone must guard the law, not as a sword, but as a trellis—something upon which life might grow upward and outward.

To be free is not to be alone. It is to be interwoven. It is to move boldly, yes, but with a line that leads home. And if this sounds old-fashioned, then perhaps it is the kind of old-fashioned we desperately need—like handwritten letters, or the ability to disagree without declaring war.

As the sun dipped behind the hedgerow that afternoon, my godson tugged on the string and said, quite proudly, “Look how high it goes!” And I, holding the reel and watching the dance of cloth against cloud, said softly, “Yes, and look how strong the string must be.”

So here is the paradox: We rise not by cutting ties, but by choosing them wisely. Freedom is not the absence of cords, but the art of being held just enough to fly.

What are the tethers that keep your freedom from becoming drift? Are there relationships, traditions, or inner disciplines that anchor you in the skyward work of living? Where might you strengthen a bond—for your own sake, and for the sake of the common wind?