On the use of soft words to mask hard realities.

We are far too polite in our cruelty.

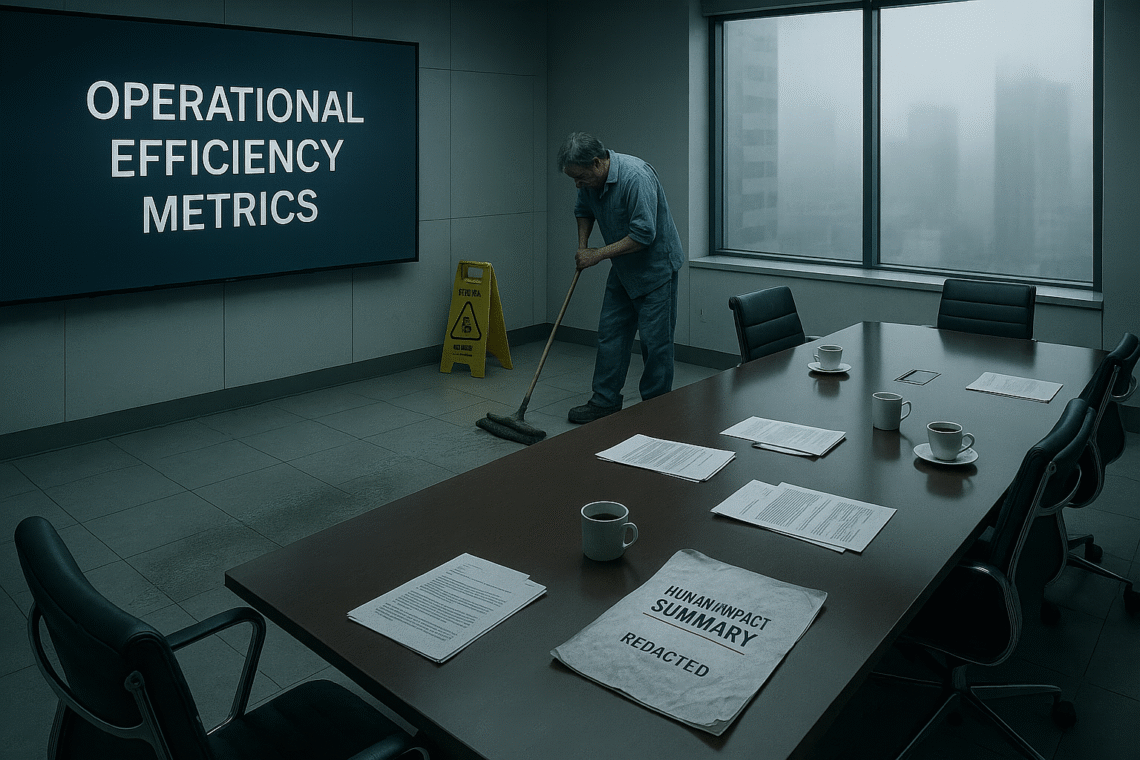

We package brutality in language so smooth, so clinical, that it barely disturbs our moral slumber. Enhanced interrogation. Collateral damage. Food insecurity. Involuntary separation. Words that glide off the tongue like silk, and yet cloak the agony of torn bodies, broken families, empty stomachs, and systems built on indifference.

One wonders what Orwell would say, if he weren’t already hoarse from spinning in his grave.

Euphemism, in its benign form, is an old and occasionally merciful friend. We say someone “passed away” instead of “died”; we speak of “letting someone go” rather than firing them. There is a time and a place for such gentleness, grief requires it, as does decency. But there is another kind of euphemism, more strategic, more institutional, and far more dangerous.

This is the language of the powerful when they wish to avoid accountability. It is the tongue of white papers and war rooms. The lexicon of distance. And it does not just dull the pain of what is described, it dulls the conscience of those who describe it.

The real danger of euphemism is not that it lies, but that it half-tells. It gives us just enough truth to remain credible, while obscuring enough to remain palatable. It is moral anaesthesia. We hear the term, and we know, somewhere beneath it, that something is wrong, but the sting has been numbed.

A drone strike that kills a family becomes a precision strike with collateral impact. A child held in a cage is part of a detention and processing protocol. A wage that cannot feed a household is a non-livable income. These phrases sound sterile, technocratic, safe. They make horror administrable.

And we, the listeners, the readers, even the preachers and poets, are lulled into a kind of trance.

We stop asking the essential questions: Who is suffering? Why? Who benefits from this silence?

There is an odd comfort in official language. It gives the illusion of order, reason, and control. A policy document sounds so much less violent than a cry for help. The former has bullet points; the latter has blood.

But it is precisely this comfort that must be disturbed. Because behind every euphemism is a human being. Behind disproportionate use of force is a bruised body. Behind negative patient outcome is a grieving parent. Behind human capital depreciation is a person discarded by an economic system.

And the longer we allow these phrases to stand uncontested, the more we participate in their violence. For language shapes what we are able to see, and what we cannot bear to look at, we eventually forget.

In the ancient world, to name a thing rightly was an act of power. It meant to see clearly, to acknowledge existence, to honour reality. The prophets of old did not speak in euphemism. They spoke in thunder. Woe to those who call evil good and good evil, cries Isaiah, who put darkness for light and light for darkness.

To speak truthfully today is to risk discomfort. It is to violate the norms of corporate speech, academic politesse, and even polite religious discourse. But if we believe that language bears moral weight, as I do, then the refusal to name suffering plainly is not gentleness. It is complicity.

I do not mean we must become brash or brutal in our speech. Truth can still be tender. But tenderness must not become timidity.

There is a kind of cleanliness to honest speech. It washes the conscience. It clarifies the world. It gives dignity to those who suffer by refusing to obscure the nature of their pain.

We must become people who practise this kind of speech. Who gently, but firmly, refuse the easy phrase. Who interrupt the soothing cadence of euphemism with the uncomfortable reality it conceals.

So here is your small act of resistance:

Choose one euphemism you’ve heard recently, perhaps in the news, a workplace email, or even your own speech. Unpack it. Ask: What does this phrase really mean? Whose pain does it hide? Whose interests does it serve?

Then, find a way to name the truth clearly. Speak it, write it, whisper it into a room that prefers silence. Say what is actually happening.

Let your words do what good words are meant to do, not just describe the world, but awaken it.